When Socorro Escalante, MD, arrived in Hanoi in 2009 as the WHO technical officer and medicines policy advisor in Vietnam, she found a country whose government had started an ambitious journey towards providing all of its citizens with reliable and accessible health care. In spite of the many challenges, the Vietnamese government has been making impressive progress.

A study prepared at the time she started had found that most essential medicines - from antibiotics and high blood pressure medicines to cancer treatments and antidepressants - were imported and priced too high to be accessible to most of the population. The Vietnamese government’s solution, recalls Dr. Escalante, was to start building the local pharmaceutical industry, thereby avoiding the high price of imported medicines.

“The government had a lot of policies in place, including a National Medicines Policy and an essential medicines list,” she notes. “But in 2009, a major priority of the government’s was to develop the local pharmaceutical sector as one of the country’s key technology industries. It was a very ambitious plan that needed some refinement.”

As Dr. Escalante met with members of Vietnam’s health ministry, she talked about the four key components of WHO’s access to essential medicines policies. Essential medicines are intended to be available within the context of functioning health systems at all times in adequate amounts, in the appropriate dosage forms, with assured quality, and at a price the individual and the community can afford. They also must be used properly.

If Vietnam wanted to grow its pharmaceutical industry to cater to the needs of its people, production and distribution had to meet all four policy requirements while also achieving economic objectives. It was a tall order, and other countries like India were already exporting essential medicines to Southeast Asia.

But WHO embraced Vietnam’s independent-minded approach and provided support. As well as adopting sound policies for the selection, supply and use of medicines, Vietnam benefitted from WHO’s knowhow and advice to build technical capacity within the health system, particularly in oversight activities to ensure that the medicines and health products supplied on national markets are of good quality, safe and effective.

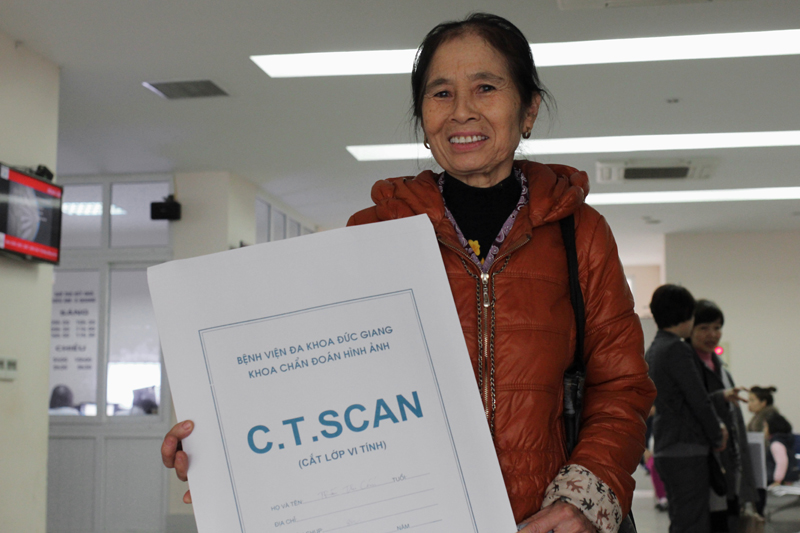

The results of that collaboration are not readily visible to the general public, especially from the ground floor of health care centres like the Duc Giang Hospital. Duc Giang serves the entire province of Hanoi and is growing constantly—its latest building was just inaugurated in January 2016 and the administration is breaking ground for the construction of two more buildings later this spring.

But while the WHO logo may be hard to find, the collaboration has produced better delivery of health products. Patients come to Dug Giang to be treated for hypertension, kidney failure and diabetes, and can now expect that the treatments they receive will be safe, effective and always available. Five years ago, the facility was housed in a much poorer building, the medicines were priced too high, and the standard of care was not as reliable.

In the hospital’s main conference room, Dr. Nguyen Thai Son, the director of Duc Giang Hospital, proudly recounts how his facility, like others in Vietnam, now follow the list of essential medicines that was developed in close collaboration with WHO. The list is updated every five years, and each version incorporates more data on the way pharmaceuticals are provided on a day-to-day basis.

“I have been working in the health sector for over 30 years,” said Dr Nguyen. “And whenever we have to implement a major policy or technical guidance, we follow WHO’s protocols, as well as their recommendations on medicines and medical equipment provided in health facilities. They are very active and provide guidance for our operations and research.”

WHO’s collaboration can also be seen on the other side of Hanoi. At the measles vaccine production facility of Polyvac, a state-owned company, Prof. Nguyen Dang Hien proudly notes that WHO certified his facility’s quality control laboratory in 2014. The director of Polyvac, Prof. Nguyen has spent his entire career working on vaccine production in Vietnam.

He is currently working on a combined measles-rubella vaccine, and can walk through in detail how this work adheres to all the norms and standards established by WHO.

“Vietnam has a long history of vaccine production, starting with the rabies and smallpox vaccines before our independence in 1945,” Prof Nguyen said. “Now, almost all of the vaccines in our expanded program on immunization are locally produced—in WHO prequalified facilities.”

Duc Giang is not the only facility in Hanoi whose services have improved. The local clinic in Hanoi’s Gia Lam District that serves Dao Duy Tuoc and his family has also grown in capacity and effectiveness. A retired farmer of 85 living with his wife, Tuoc receives medication for hypertension but is still healthy and independent.

“We have seen a lot of positive changes in our healthcare system,” he points out after a recent visit to update his prescription. “The quality of care has improved dramatically and doctors and nurses have been trained with new skills and abilities.”

Luong Ngoc Khue, MD, PhD, Director of Vietnam’s Medical Service Administration, has long been appreciative of WHO’s assistance and partnership, which has helped Vietnam to select, manage and quality-assure the medicines on its market, while ensuring access and affordability.

“Our work every year is supported not just by the government but also by WHO,” he says. “Every year we meet, hold workshops, and exchange information with WHO—both their regional office and the headquarters in Geneva.”

Dr. Khue of the Medical Services Administration and Dr. Escalante both appreciate Vietnam’s progress, but they also stress that the partnership needs to continue. More work is needed to achieve universal access to quality essential medicines and health technologies.

“Our charge is to take care of the health of the Vietnamese population - 92 million people,” Dr. Khue says. “We are very proud of what we have achieved but there are still a lot of challenges that need to be met.”