Treatment

Early access to medical care in a health facility that has personnel trained and capable of diagnosing snakebite envenoming is essential. This means, a health centre which is equipped with the basic resources needed to provide immediate emergency treatment needs, including the administration of antivenom and other adjunct therapy.

People who suspect they have been bitten by a venomous snake should be transported to a health facility without delay. First aid should be applied (see Box 1). Traditional medicines and other treatments such as wound incision or excision, suction, or application of “black stones” should be avoided.

Many people die every year on the way to a health facility as a result of being transported lying flat on their backs and having their upper airway obstructed by vomit, or paralysis of muscles in the tongue. Keep them on their left side with mouth turned down so that the risk of this is reduced.

Health facilities should treat all snakebite cases as emergencies and give priority to assessing these patients and instituting treatment without delay.

Improving the clinical outcomes for the victims of snake bite needs much more than just access to safe antivenoms. Intravenous access should be achieved early, hydration state determined and corrected if needed, and vital signs must be closely monitored. The early administration of an adequate dose of effective antivenom to patients with signs of envenoming is crucial. If no antivenom is available, referral to a centre which has supplies should be planned and undertaken quickly. If this is not possible then symptomatic treatment including support of airway patency and breathing, maintenance of circulation and control of bleeding, and the treatment of local wounds should be prioritized as appropriate.

Administered early, antivenoms are not just life-saving, but can also spare patients some of the suffering caused by necrotic and other toxins in snake venom, leading to faster recovery, less time in hospital and a more rapid transition back to a productive life in their communities. But the reality for many patients is that early access to antivenom is simply not possible for a multitude of reasons (see Box 2). As a consequence, these patients do not receive the full potential benefit of antivenom, and some of the effects of the snake venom may not be neutralized effectively, leading to prolonged illness, slower recovery and greater risk of disability. For those affected by toxins that cause paralysis, sustained airway and breathing assistance using either manual resuscitators or mechanical ventilators may be necessary. Patients bitten by snakes with venom that affects normal blood clotting may have a higher risk of internal bleeding into the brain and other organs, and those affected by dermonecrotic toxins will experience more severe local tissue damage.

Box 1. First aid for snakebites

If you suspect a snake bite:

- Immediately move away from the area where the bite occurred. If the snake is still attached use a stick or tool to make it let go. Sea snake victims need to be moved to dry land to avoid drowning.

- Remove anything tight from around the bitten part of the body (e.g.: rings, anklets, bracelets) as these can cause harm if swelling occurs.

- Reassure the victim. Many snake bites are caused by non-venomous snakes. And even after most venomous snake bites the risk of death is not immediate.

- Immobilize the person completely. Splint the limb to keep it still. Use a makeshift stretcher to carry the person to a place where transport is available to take them to a health facility.

- Never use a tight arterial tourniquet.

- The Australian Pressure Immobilization Bandage (PIB) Method is only recommended for bites by neurotoxic snakes that do not cause local swelling.

- Applying pressure at the bite site with a pressure pad may be suitable in some cases.

- Avoid traditional first aid methods, herbal medicines and other unproven or unsafe forms of first aid.

- Transport the person to a health facility as soon as possible

- Paracetamol may be given for local pain (which can be severe).

- Vomiting may occur, so place the person on their left side in the recovery position.

- Closely monitor airway and breathing and be ready to resuscitate if necessary.

Box 2. Barriers to Early Antivenom Access

Some of the key contributors to delayed antivenom treatment include:

- Distance from location where people are bitten to the nearest health facility with antivenom.

- Cultural barriers influencing health-seeking behaviour.

- Lack of transportation; many victims have to walk long distances further delaying treatment and accelerating venom effects.

- Absence of cold-chain storage for antivenoms and other medicines in rural health facilities.

- Stock shortages or lack of any stock at all.

- Usage restrictions that prevent antivenom from being administered in primary health centres, forcing victims to look for treatment somewhere else.

- High costs of antivenoms can lead to delays while family members look for funds.

Antivenom treatments

Antivenoms remain the only specific treatment that can potentially prevent or reverse most of the effects of snakebite envenoming when administered early in an adequate therapeutic dose. They are included in WHO’s Model List of Essential Medicines.

Early access to safe, affordable and effective antivenoms is critical for minimizing morbidity and mortality, and improving this access is a major component of an emerging WHO strategy to control snakebite envenoming.

Additional therapy to treat envenoming

In addition to antivenom, additional medical measures, including administration of other drugs, artificial respiration, kidney dialysis, wound care, reconstructive surgery and prosthesis as well as comprehensive rehabilitation services, are needed to effectively treat snakebite patients. A class of drugs known as anticholinesterases can be beneficial in restoring neuromuscular function after the bites of some species of neurotoxic venomous snakes.

Several drugs are also being explored for their potential to act as anti-necrotic agents, reducing the local tissue damage that can lead to severe disability and even amputation, after some snake bites.

Diagnostic tests and tools

At present there is only one commercial diagnostic test available that makes it possible to confirm the type of snake venom present in the body of an envenomed patient. This test uses antibodies to recognize specific types of venom produced by different species of snakes.

Other diagnostic tests that use similar approaches are being used experimentally, but there is a need in some regions and countries for commercial tests that can be used to better inform the proper selection of antivenoms to treat patients.

There are however simple tests and diagnostic tools (algorithms or checklists) that can be used to confirm the presence of important clinical signs of snakebite envenoming which indicate the need for early antivenom treatment and, in some cases, can help differentiate the most likely genus or species of snake responsible for the bite.

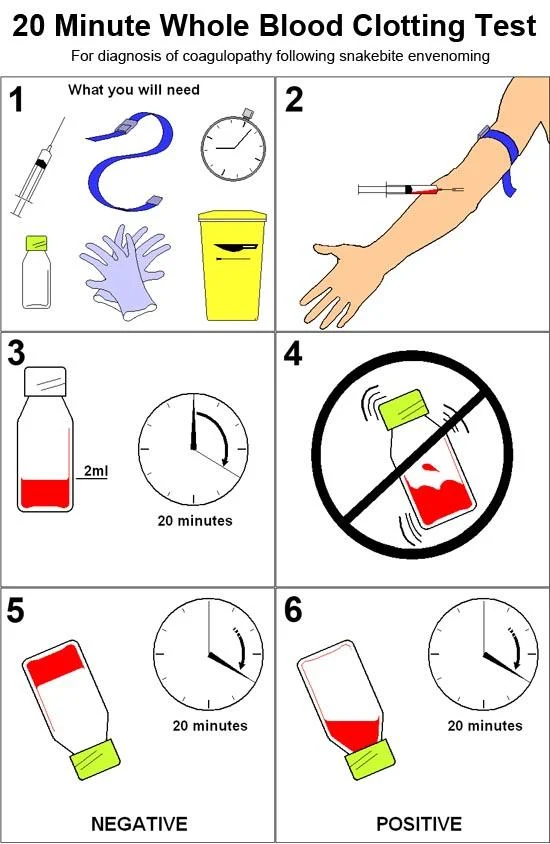

Spontaneous haemorrhage due to envenoming by some snake species is an important clinical indication for antivenom. Diagnosis is aided by a test known as the 20 Minute Whole Blood Clotting Test (20WBCT). A clean, dry glass bottle or vial into which 1-2 millilitres of venous blood is added, is allowed to stand at room temperature for 20 minutes, and is then inverted and the presence or absence of a complete clot is recorded. Where a blood is present, the test result is negative, whereas if no clot forms and the blood remains liquid, the test result is positive, indicating presence of a coagulopathy and the need for antivenom treatment. Where this test is used it is essential that it be appropriately standardized using uniform glassware, sample volume and temperature, and validated for accuracy using serial donor samples prior to routine use.

Diagnostic tools also have considerable potential to better inform the surveillance of snakebite envenoming by enabling retrospective identification in pathology samples of venom immunotypes from various species of snakes. This can improve the reporting of snakebite envenoming and assist in determining optimal antivenom needs for regions.

Rehabilitation

According to the WHO World Report on Child Injury Prevention (2008), there may be as many as 400,000 cases of snakebite each year where disability is caused by the effects of the injected venom. Many snakes have dermonecrotic, cytotoxic, myotoxic or haemorrhagic components in their venoms, causing disabilities ranging from local skin, muscle and connective tissue destruction.

Snake bites can cause a variety of disabilities ranging from skin and soft tissue injury that causes scarring, to deeper muscle, connective tissue and vascular necrosis and gangrene leading to substantial loss of limb use or even amputation. Poor wound healing can lead to disfiguring contracture and permanent loss of function. Spitting cobras can spray venom into the eyes causing conjunctivitis, corneal ulceration and erosion and, ultimately, blindness. Some toxins in snake venoms can cause effects that indirectly damage the normal function of the kidneys, resulting in a need for long-term haemodialysis or even kidney transplantation. All of these types of injury require prolonged hospital treatment and extensive rehabilitation.

Currently there are no specific resources allocated anywhere in the world to dealing with this problem. In some countries victims are reduced to lives of poverty and may be socially ostracized because of horrendous physical deformities caused by the bites of venomous snakes. Addressing this enormous problem needs to be a core component of any strategy to improve the treatment and the outcomes of snake bites. Raising awareness of the problem with existing organizations that work with disabled people in the developing world is an important component to improving access and equity for snakebite victims.

Improving treatment for snakebite patients

Apart from the provision of safe, effective and affordable antivenoms, the most important step towards improving the treatment of snakebite envenoming is providing proper education and training to medical staff and health-care workers in countries where snakebite is common.

Many medical schools do not have substantive training modules on snakebite included in their curriculums. Furthermore, nursing schools and colleges offering health-care education may lack good teaching information on the subject.

Skills that are taught to medical personnel for treating snakebite often have relevance to other health problems. Resuscitation skills taught to doctors who treat neurotoxic snake bites can be of great assistance in improving outcomes for many conditions such as asthma, head injuries or road trauma, and patients suffering from other noncommunicable acute illnesses.

WHO has already helped to address this problem by supporting the development of standard treatment Guidelines in its South-East Asia and African regions. These documents provide valuable information for medical professionals and health-care workers. It is hoped that additional training resources for regions and individual countries will take into account particular service delivery environments and local resource availability.

These guidelines, prepared by experts with many years of experience treating snakebite envenoming in both regions are essential tools to improving the care and treatment of snake bite victims in Asia and Africa.

Guidelines for the management of snakebites, 2nd edition

Snakebites are well-known medical emergencies in many parts of the world, especially in rural areas. Agricultural workers and children are the most affected....

Snakebite is a neglected public health problem. Rural populations are frequent victims as they go about their daily food production and animal rearing...

Related activity

Related health topics