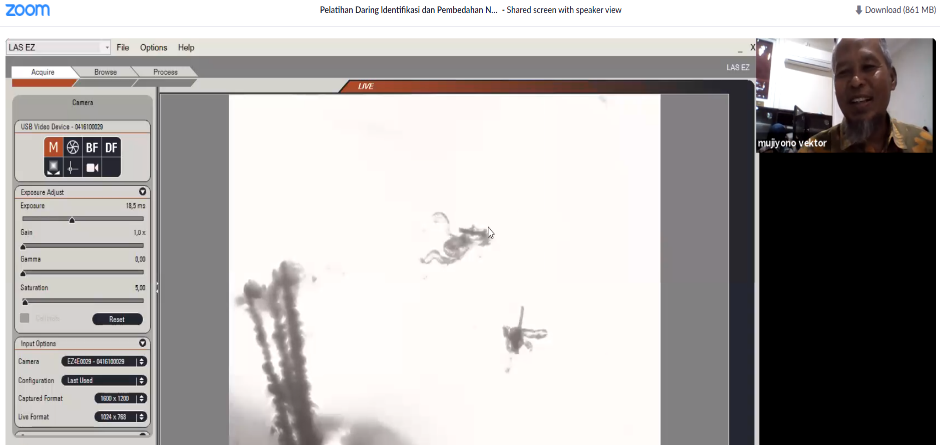

Caption: Demonstration of setting up WHO susceptibility test kits for measuring insecticide resistance in a virtual training for health entomologists

Credit: WHO IndonesiaVector control is a critical component in the global strategy to end malaria. Despite the COVID‑19 pandemic, the Ministry of Health (MoH) and WHO continued the fight against malaria with capacity building initiatives in vector control for entomologists.

Between 9 November to 16 December 2020, WHO supported the Subdirectorate of Vector and Animal Reservoir Control, MoH, to conduct a series of virtual training sessions to strengthen the vector and animal surveillance system and control interventions. The six series of three-day training batches were each attended by 60-85 entomologists from the provincial and district health office, the Environmental Health and Disease Control Centre, and health port authorities across Indonesia.

The virtual training series aimed to improve participants’ knowledge and skills on specific topics related to the vector and animal surveillance system and control interventions. The six topics delivered in the virtual training were: insecticide resistance test using WHO susceptibility method and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) bottle bioassay; mosquito identification and dissection; mice identification and dissection; operation and maintenance of vector control machines (fogger and ultra-low volume spray (ULV) fogger); vector surveillance information system (SILANTOR); and writing scientific papers for the field of entomology and parasitology. The trainers of these trainings were from the national expert committee of vector and animal reservoir control, universities, and the National Institute of Vector and Animal Reservoir Research and Development (BBPPVRP), Salatiga, Central Java.

In his remarks, the MoH Director of Vector Borne and Zoonotic Diseases Prevention and Control Dr Didik Budijanto conveyed his appreciation to the trainers and encouraged participants to ensure knowledge transfer to their colleagues in the office and apply the new knowledge and skills in their work.

Despite the limitation of virtual training, participants’ knowledge has improved from 15% to 25% in the post-training test compared to the mark in the pre-training test.

The first and second series of the training were relevant to malaria and arbovirus surveillance. The first training discussed routine surveillance of insecticide-based control interventions such as long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLIN), indoor residual spraying (IRS) and space spraying. According to WHO recommendations for malaria and dengue-endemic countries, monitoring insecticide resistance should be institutionalised and conducted regularly.

Caption: Trainer from BBPPVRP Salatiga demonstrated the method of mosquito species identification using trinocular stereo microscope with camera.

Credit: WHO Indonesia

In the second training, participants learned how to identify and dissect mosquitoes to differentiate their genus and species. This topic is relevant for mosquitoes-borne disease surveillance to determine the vectors of diseases transmission.

The third training highlighted the importance of mice surveillance as animal reservoir of leptospirosis, teaching participants how to identify the mice by colour, size, number, genus and species.

Entomologists were trained to operate and maintain a vector control machine (fogger and ULV fogger) during the fourth training. This training is critical to interrupt further dengue transmission in the community.

Health entomologists were trained on recording, reporting, and analysing data on vector surveillance during the fifth training. Using the web- and mobile-based vector surveillance information system (SILANTOR) application, all routine vector surveillance data can be recorded and reported up to the national level. The data and evidence from this application can be utilised to update the distribution of vectors in Indonesia and inform the policy on vector control interventions using available evidence.

In Indonesia, entomologists are required to actively analyse and report vector control and surveillance data and publish their findings in scientific journals. To this end, the sixth training provided an introduction to writing scientific manuscripts in the field of entomology and parasitology.

As a way forward, all participants were encouraged to not only conduct proper routine surveillance, but also report through the SILANTOR application and publish the findings in peer-reviewed scientific journals. The series of training is part of the WHO and MoH’s strategy to enhance the capacity of entomologists in responding to the changing threats and opportunities for reducing transmission of malaria and other vector-borne diseases and improving health outcomes.